A short biography of robert e. howard

By Rusty Burke

Robert Ervin Howard (1906-1936) ranks among the greatest writers of action and adventure stories. The creator of Conan the Cimmerian, Kull of Atlantis, Solomon Kane, Bran Mak Morn, ‘El Borak,’ Sailor Steve Costigan and many other memorable characters, Howard (known as REH to his millions of fans), in a career that spanned barely 12 years, wrote well over a hundred stories for the pulp magazines of his day.

While he is widely regarded as the ‘father of Sword and Sorcery’ and the creator of Conan the Barbarian, this reputation has been something of a double-edged sword. It has helped keep his work in the public eye for six decades since his death, but it has also obscured the astonishing breadth of his imagination, his talent for mastering a variety of genres and his ability to weave his magic in both prose and poetry.

Robert E. Howard contributed his most celebrated work to the pre-eminent fantasy pulp magazine of the era, Weird Tales. However, his stories also appeared in such diverse publications as Action Stories, Argosy, Fight Stories, Oriental Stories, Spicy Adventure, Sport Story, Strange Detective and a number of others. That his stories were a consistent hit with readers of the time is not surprising, for he created thrilling, vividly realized adventures populated by colorful, larger-than-life characters.

He was a consummate and dynamic storyteller. Even after his death publishers continued for some time to publish his stories or reprint them under other by-lines. So enduring is the appeal of his work that over a half century later he continues to gain new fans, introduced to his tales through paperbacks, comics, and movies.

His work has also inspired subsequent generations of fantasy writers and a loyal following that has taken to cyberspace to spread the word.

Robert E. Howard was born on January 22 (or possibly January 24), 1906, in the “fading little ex-cowtown” of Peaster, Texas, in Parker County, just west of Fort Worth. The confusion surrounding his date of birth arises from Howard celebrating January 22 as his birthday (this was the date he submitted to Who’s Who Among North American Authors), while his record of birth in Parker County reads January 24. As his father also gave Robert’s birthday as 22 January, it is probably safe to assume that is the correct date.

At the time of Robert’s birth, the Howards lived in Palo Pinto County, on the banks of Dark Valley Creek. His father, Dr. Isaac Mordecai Howard, presumably moved his wife temporarily to the larger community of Peaster to allow readier access to medical care during her pregnancy. Hester Jane Ervin Howard, Robert’s mother, did not enjoy robust health, to put it mildly: there was a history of tuberculosis in her family and Hester Howard was sickly for much of Robert’s life. Isaac Howard was a country doctor, a profession that entailed frequent lengthy absences from home, and thus he may have wished to be certain that his wife of two years would have adequate medical attention when she delivered their first, and as it transpired, only child.

Isaac Howard seems to have been possessed of a combination of wanderlust and ambition that led him to frequently move his family in search of better opportunities. By the time he was eight, Robert had lived in at least seven different and widely scattered Texas towns. In 1915, the family moved to the community of Cross Cut in Brown County, and they would live in this vicinity – with moves to Burkett (in Coleman County) in 1917 and finally to Cross Plains (Callahan County) in 1919 – for the rest of Robert’s and his mother’s lives.

Cross Plains in the 1920s was a small town of approximately 2000 people, give or take a thousand. Like much of the Central West Texas region, though, it went through periodic oil booms that brought hundreds, perhaps thousands, of temporary inhabitants who set up camps just outside the town limits, jammed the hotels beyond capacity, and rented rooms or beds in private homes. The lease men, riggers, drillers, tool dressers, and roughnecks who followed the oil were followed in their turn by others who sought to make a quick buck off them, from men or women who set up temporary hamburger stands to feed them, to gamblers and whores who provided “recreation,” to thugs, thieves and con men who simply preyed on them. An oil boom could transform a sleepy little community into a big city in no time at all, in those days, and bring with it much social upheaval. The few extra thousand who swelled the population of Cross Plains managed to make it a far wilder and rowdier town than usual.

One resident recalls her family driving into town on Saturday night just to watch people, hoping fights would break out. Of the atmosphere in a boom-town, Howard wrote: “I’ll say one thing about an oil boom: it will teach a kid that life’s a pretty rotten thing about as quick as anything I can think of.” Just as fast as the town grew, however, it could decline: when the oil played out, the speculators, oil-field workers and their camp-followers moved on. The influence of this boom-and-bust cycle on Howard’s later ideas about the growth and decline of civilization — that societies are built by hardy pioneers, who are then followed by others who grow decadent and enjoy the fruits of the society but contribute nothing to its continued growth, and thus inevitably the society will decay or be overthrown by a new generation of pioneers — has often been overlooked.

Robert Howard attended the local high school, where he was remembered as polite and reserved. To make pocket money he labored at a variety of jobs, including hauling trash, picking up and delivering laundry for dry-cleaners, working as a store clerk and loading freight at the train station. He had some close friends among the local boys, but none shared his literary interests, which had probably been nurtured from an early age by his mother, an ardent lover of poetry. He was an avid reader, claiming even to have raided schoolhouses during the summer in his quest for books. While this story is no doubt exaggerated, it demonstrates his love of reading, a rarity in these outlying communities, most of which had no libraries, much less bookstores. Howard devoured books at an extraordinary rate, astonishing his friends with his ability to pick up a book and turn the pages faster than they thought anyone could actually read. Yet later he could remember what he had read with perfect clarity. His friend Lindsey Tyson claimed that Howard had memorized ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ after only two readings.

Howard’s library, presented by his father to Howard Payne College after his death, reveals the breadth of his interests: history and fiction are dominant, but also represented are biography, sports, poetry, anthropology, Texana and erotica. Near the end of his life, Howard wrote to the renowned fantasist H.P. Lovecraft, with whom he corresponded regularly, about his favorite writers. These included Arthur Conan Doyle, Jack London, Mark Twain, Sax Rohmer, Talbot Mundy, Harold Lamb, H. Rider Haggard, Rudyard Kipling, Sir Walter Scott, Ambrose Bierce, Edgar Allan Poe and Lovecraft. A huge fan of poetry, Howard also sought out the verse of Robert W. Service, Kipling, Sidney Lanier, Poe, Walter de la Mare, Omar Khayyam, Henry Herbert Knibbs, G.K. Chesterton, Oscar Wilde, Tennyson, Alfred Noyes and Lovecraft, among many others.

In addition to his reading, Robert Howard had a passion for oral storytelling. It is well attested that he frequently told his stories aloud as he typed them, annoying his neighbors no end with the racket he often made right through the night. His buddies in Cross Cut also recall that he liked to have them play out stories he made up, just as he would later regale the literary friends of his adulthood with his more elaborate tales. He seemed never to tire of telling stories, though generally he would not talk about material on which he was actually working. He told his friend Novalyne Price that once the story was told, he had difficulty getting it on paper. Sometimes, however, his oral tales would provide the inspiration for stories he would later write. Howard also relished listening to others tell stories. His letters reveal how, as a young boy, he was thrilled and terrified by the ghost tales of the family cook, a former slave, and those of his grandmother. He would also seek out old-timers and persuade them to share their memories of the pioneer days. It may well be the quality of the well-spun yarn that gives Howard’s stories their immediacy.

Howard seems to have decided upon a literary career at an early age. In a letter to Lovecraft he says that his first story was written when he was “nine or ten,” and a former postmistress at Burkett recalls that he began writing stories about this time and expressed an intention of becoming a writer. He submitted his first story for publication when he was only 15, and made his first professional sale – ‘Spear and Fang,’ a short story in which a Cro-Magnon rescues his mate from a Neanderthal – at the ripe old age of 18. Howard always insisted that he chose writing as his profession simply because it gave him the freedom to be his own boss: “I could have studied law, or gone into some other occupation, but none offered me the freedom writing did – and my passion for freedom is almost an obsession…. Personal liberty may be a phantom, but I hardly think anybody would deny that there is more freedom in writing than there is in slaving in an iron foundry, or working – as I have worked – from 12 to 14 hours, seven days a week, behind a soda fountain. I have worked as much as eighteen hours a day at my typewriter, but it was work of my own choosing…. I’ve always had a honing to make my living by writing, ever since I can remember, and while I haven’t been a howling success in that line, at least I’ve managed for several years now to get by without grinding at some time clock-punching job.” Whatever his reasons, once Howard had determined upon his path, he was completely committed to it, despite the obstacles. As he later said to H.P. Lovecraft, “…It is no light thing to enter into a profession absolutely foreign and alien to the people among which one’s lot is cast; a profession which seems as dim and faraway and unreal as the shores of Europe…. The idea of a man making his living by writing seemed, in that hardy environment, so fantastic that even today I am sometimes myself assailed by a feeling of unreality. Never the less, at the age of fifteen… having only the vaguest ideas of procedure, I began working on the profession I had chosen.”

The Cross Plains school only went through to tenth grade at the time Robert Howard attended, but he needed to complete the eleventh grade to qualify for college admission. Thus in the fall of 1922, when Robert was 16, he and his mother moved to Brownwood, a larger town that served as the county seat for Brown County, so that he could finish high school. It was there that Howard met Truett Vinson and Clyde Smith, who would remain his friends until the end of his life. They were the first of his friends to encourage his interest in literature and writing, and Smith, especially, shared Howard’s fondness for poetry. It was also at Brownwood High that Howard first enjoyed the thrill of being a published author: two of his stories won cash prizes and publication in the high school paper, The Tattler (December 22, 1922), and three more were printed during the spring term.

After his graduation from high school, Howard returned to Cross Plains. His father, in particular, wanted him to attend college, perhaps hoping that he would follow in his footsteps and become a physician. But Robert had little aptitude for and no interest in science. He also detested school, as he explained later to Lovecraft: “I hated school as I hate the memory of school. It wasn’t the work I minded; I had no trouble learning the tripe they dished out in the way of lessons – except arithmetic, and I might have learned that if I’d gone to the trouble of studying it. I wasn’t at the head of my classes – except in history – but I wasn’t at the foot either. I generally did just enough work to keep from flunking the courses, and I don’t regret the loafing I did. But what I hated was the confinement – the clock-like regularity of everything; the regulation of my speech and actions; most of all the idea that someone considered himself or herself in authority over me, with the right to question my actions and interfere with my thoughts.” Although he did eventually take courses at the Howard Payne Commercial School, these were business courses in stenography, typing and bookkeeping. Despite his interest in history, anthropology and literature, Howard never took college courses in these subjects.

During the period from his high school graduation in the spring of 1923 to his completion of the bookkeeping program in the spring of 1927, he continued writing. While he finally made his first professional sale during this period, when Weird Tales accepted ‘Spear and Fang,’ he also accumulated many rejection slips. Weird Tales did publish other of his stories: ‘In the Forest of Villefere,’ a short werewolf tale, appeared in August 1925 (the month after ‘Spear and Fang’ finally appeared), ‘Wolfshead,’ a somewhat longer sequel to ‘Villefere,’ in April 1926, and ‘The Lost Race,’ a story of early Britain, in January 1927. Because Weird Tales paid upon publication rather than acceptance, though, the young author found that the money was not coming in as fast as he would have liked, so he took a variety of jobs during these years. He tried reporting oil-field news, but found he did not like interviewing people he did not know or like about a topic that did not interest him. He tried stenography, both as an employee and as an independent public stenographer, but found he was not particularly good at it and gave it up. He worked as an assistant to an oil-field geologist, and though he enjoyed the work, he collapsed one day in the fearsome Texas summer heat. The incident led him to fear that he had heart problems, and it was later learned that his heart did have a mild tendency to race under stress, so he was just as glad when the survey ended and the geologist left town. When he received his advance proofs of ‘Wolfshead,’ he became disheartened, and immediately took a job as a soda jerk and counterman at Robertson’s Drug Store, a job that he despised and which required so much of his time that he had little left over for writing or recreation. He therefore made a pact with his father: he would take the course in bookkeeping at Howard Payne, following which he would have one year to try to make a success of his writing. If that didn’t work out, he would try to find a bookkeeping position.

During the summer of 1927, Robert Howard met Harold Preece, who would become an important friend and correspondent over the next few years. It was Preece who rekindled Howard’s interest in Irish and Celtic history and legend. During the same weekend he also met Booth Mooney, who became the editor of a literary circular, The Junto, to which Howard, Preece, Clyde Smith, Truett Vinson and others contributed over a period of about two years.

After completing the bookkeeping course, Howard set about in earnest to become a professional writer. By early 1928, it was clear that he would be able to succeed, and indeed he never again worked at any other job. In 1928, Weird Tales published four stories (including the first Solomon Kane tale, ‘Red Shadows’) and five poems. From then until his death in June 1936, Howard stories or verse appeared in nearly three of every four issues of the magazine.

Writers working for the pulp magazines had two paths to success. One was the creation of a character who would keep readers coming back for more and thus keep editors happy. The second was versatility; a writer who could handle a variety of story types could sell to more magazines in an age of specialization. Howard agreed with one correspondent that “the pulp magazines are specializing to an alarming rate… Wild West Weekly, Battle Stories, Gangster Stories, Two-Gun Stories (!) and Wall-Street Stories being a few of the titles of magazines now seen on the newsstands”.

Fortunately, Robert E. Howard was both versatile and had the knack of creating popular characters. However, unlike many of his contemporaries, who could continue cranking out stories about their characters long after inspiration had abandoned them, Howard found he could not keep a series going indefinitely. Writing to Clark Ashton Smith in 1933 about Conan, he conceded “the time will probably come when I will suddenly find myself unable to write convincingly of him at all. This has happened in the past with nearly all my numerous characters; suddenly I would find myself out of contact with the conception, as if the man himself had been standing at my shoulder directing my efforts, and had suddenly turned and gone away, leaving me to search for another character.” After Howard’s death, H.P. Lovecraft said that the secret to the vividness of Howard’s stories was “that he himself is in every one of them.” Less perceptive critics have suggested that Howard’s heroes were all essentially cut from the same cloth, but if this were true, Howard should have had no problem continuing to write stories about Kull, Solomon Kane, Bran Mak Morn and the like. Howard scholar Patrice Louinet has proposed what seems the best explanation for this: that the characters represent new stages of the writer’s own emotional growth. As a person matures, his basic nature or personality does not change dramatically (thus the similarities among the characters), but many of his ideas and his emotional responses to the world do change (and thus the contemplative and sometimes tentative Kull comes to be replaced by the more carefree and decisive Conan, to use one example). Howard sometimes lost touch with his characters, then, because he had psychologically outgrown them, and could therefore no longer write convincingly from their point of view.

A very interesting character, from this psychological standpoint, is Francis Xavier Gordon, a.k.a. ‘El Borak’. According to Howard, Gordon was first created when he was only ten, though it was some time before his exploits were committed to paper. In the earliest surviving stories, written by a teenage Howard, Gordon is a world traveler and adventurer, a man known to and respected by the British Secret Service. He may have been inspired by such real-life men of action as Richard Francis Burton, John Nicholson and ‘Chinese’ Gordon. As they exist today, none of these early stories is complete. It was not until years later, in December 1934, that this former Texas gunslinger turned Middle Eastern adventurer appeared in ‘The Daughter of Erlik Khan’ in Top-Notch. Gordon clearly reflected the youthful Howard’s infatuation with the Orient, echoing the exploits of Lawrence of Arabia and the fiction of Talbot Mundy. Just why this character should have languished for at least ten years, even after Howard began writing for Oriental Stories in 1930, remains something of a mystery, but it is interesting to compare the sophisticated world traveler of the earliest stories with the hardened frontier fighter of the later tales.

The young Howard next turned to ancient Britain for the creation of Bran Mak Morn. When Robert was 13, his father took the family to New Orleans, where the doctor enrolled in a post-graduate medical course. While there, Robert sought out a public library and discovered a book on British history in which he learned of a small, dark race of Mediterraneans who settled in the British Isles before the arrival of the Celts. These people were called Picts, and they strongly appealed to young Robert’s imagination. “The writer painted the aborigines in no more admirable light than had other historians whose works I had read. His Picts were made to be sly, furtive, unwarlike and altogether inferior to the races which followed – which was doubtless true. And yet I felt a strong sympathy for this people, and then and there adopted them as a medium of connection with ancient times. I made them a strong warlike race of barbarians, gave them an honorable history of past glories, and created for them a great king – one Bran Mak Morn.”

As with El Borak, it would yet be some time before Bran’s exploits were written down. The earliest mention of this character is in a 1923 letter to his friend Tevis Clyde Smith, in which Howard names Bran among several characters in a book he is writing (which apparently does not survive). One of Howard’s early sales to Weird Tales, ‘The Lost Race,’ deals with the Picts, but the chieftain in the story is named Berula, rather than Bran. In early 1926 Howard wrote ‘Men of the Shadows,’ in which Bran is a great chief, but not a king. It was only in 1930, when he wrote ‘Kings of the Night,’ that Howard made Bran a king… and more than a king. In that year, Howard also wrote ‘The Dark Man,’ a story set in the 11th century, in which Bran is said to have become a god to the remnants of the Pictish race. Curiously, while the central character in most of Howard’s stories would also be said to be the viewpoint character (even when the story is told in third person), in the Bran stories this is not the case. Howard himself recognized this, telling Lovecraft, “Only in my last Bran story, Worms of the Earth, did I look through Pictish eyes, and speak with a Pictish tongue!” This story, one of Howard’s very best, was also the last in which Bran would appear.

At the age of 16, Howard dreamed up another character, Solomon Kane, a Puritan swashbuckler who travels the world avenging wrongs. “He was probably the result,” said Howard, “of an admiration for a certain type of cold, steely-nerved duellist that existed in the sixteenth century.” As with El Borak and Bran Mak Morn, his adventures were not immediately transcribed, but in the fall of 1927, Howard completed a story called ‘Solomon Kane,’ in which his hero tracked the villainous Le Loup from a European forest to a final confrontation in the sorcery-haunted African jungle, and submitted it to Argosy All-Story, one of the top pulp markets for fiction. He was considerably heartened when he received a personal note from the associate editor, telling him what was wrong with the story, but saying “You seem to have caught the knack of writing good action & plenty of it into your stories.” Howard told Clyde Smith that he had originally written the story for Weird Tales but decided to try his luck with Argosy first; he did in fact send it on to Weird Tales unchanged. It was accepted, but he was asked to come up with another title. The story appeared in August 1928 as ‘Red Shadows.’

In some ways, Kane is one of Howard’s most complex and fascinating characters. His exploits seem to take place largely during the reign of Elizabeth I, and while some stories are set in England and the Continent, it is in Africa Kane faces his greatest challenges. Among his African encounters are the discovery of an ancient Atlantean colony now ruled by a sensuous yet degenerate queen (‘The Moon of Skulls’), a tribe of zombies (‘The Hills of the Dead’) and a village menaced by winged harpies (‘Wings in the Night’). Throughout his adventures, Kane is convinced he is a servant of God, even as he carries a ju-ju staff given him by his blood-brother N’Longa, the “mighty worker of nameless magic” first encountered in ‘Red Shadows.’ According to his creator, “all his life [Kane] had roamed about the world aiding the weak and fighting oppression; he neither knew nor questioned why. That was his obsession, his driving force of life…. If he thought of it at all, he considered himself a fulfiller of God’s judgment, a vessel of wrath to be emptied upon the souls of the unrighteous.” Through the whole series, Kane’s sense of divine purpose is tempered by his conscience and guilt over his own lust for excitement. Kane was the first character Howard sustained beyond a published story or two: seven of the Kane tales appeared in Weird Tales between 1928 and 1932, and he remains a favorite with readers and fellow writers alike.

According to Howard’s semi-autobiographical novel Post Oaks and Sand Roughs, sometime in the fall of 1926, while he was taking the bookkeeping course at the Howard Payne Academy, he began “a wild fantasy entitled ‘The Phantom Empire,’ which he laid aside partly finished and forgot about.” The following summer, “He came upon ‘The Phantom Empire,’ deserted several months before, completed it, and then again laid it aside and forgot about it.” Soon afterward, he “again discovered ‘The Phantom Empire,’ rewrote it, and again laid it aside.” In September 1927, he finally submitted the story to Weird Tales, and a short time later it was accepted, with a promised payment on publication of $100.00 – the largest sum Howard had been offered to that time. It would be over a year before this story saw publication in August 1929. The title as given in Post Oaks and Sand Roughs is, of course, thinly disguised: the story was ‘The Shadow Kingdom,’ the first published appearance of King Kull, and the tale generally regarded as the first true example of “sword and sorcery” fiction – the melding of heroic adventure with elements of fantasy and horror.

Howard said, “King Kull differed from the others (i.e., El Borak, Bran Mak Morn and Solomon Kane) in that he was put on paper the moment he was created, whereas they existed in my mind years before I tried to put them in stories. In fact, he first appeared as only a minor character in a story which was never accepted. At least, he was intended to be a minor character, but I had not gone far before he was dominating the yarn.” That initial glimpse of Kull was evidently in ‘Exile of Atlantis,’ which appears to have been written during the first half of 1925, when Howard was but 19. This slight tale relates how a young Kull grants the boon of a quick death to a woman about to be burned at the stake, thus violating tribal custom and forcing him into exile. The confining nature of traditions, customs, taboos and laws is a frequent theme in the Kull stories. In this story we learn that Kull was adopted by the Sea-Mountain tribe of Atlantis after he was found wandering in the woods. He knows nothing of his parentage, but he has a dream in which he is hailed as king of Valusia, the greatest civilization of his age.

For the Kull stories, Howard, for the first time, created a ‘Pre-Cataclysmic’ age of the earth, an age long before the dawn of recorded history. Atlantis and Lemuria had not yet vanished into the seas, but they were inhabited not by the advanced, utopian civilizations claimed by the occultists, but by savages. It was the Thurian continent that boasted grand civilizations, as well as mysterious pre-human races. The first published Kull story, ‘The Shadow Kingdom,’ deals with one of these pre-human races, and is a masterpiece of pure paranoia. It centers upon a conspiracy by a race of Serpent Men to kill the king and, by taking on the semblances of Kull and his chief councilors, to seize control of the ancient kingdom of Valusia.

In this story Kull first meets Brule, a Pictish warrior who will become his friend and comrade-at-arms throughout the rest of the series. Together they uncover and foil the conspiracy in a climax that shows Howard at his apocalyptic best. Only one other King Kull tale was published during Howard’s life, ‘The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune,’ a poetic fable heavy on metaphysical contemplation, which was published a month after ‘The Shadow Kingdom.’ Although Howard completed at least six other Kull stories, some of which are fine examples of the sword and sorcery genre, none saw publication. In 1934, when H.P. Lovecraft praised the Kull tales and urged him to write more, Howard said that he believed if he tried to write another, the “artificiality… would be apparent.” After Howard’s death, Lovecraft commented to fellow pulp scribe E. Hoffmann Price that “the King Kull series probably forms a weird peak” in the young Texan’s career, a judgment in which other writers of heroic fantasy have concurred.

If 1928 was Howard’s breakout year in Weird Tales, 1929 was a watershed for another reason. In that year the 23-year-old writer began to sell to other magazines, initially with strange tales of pugilism. Under the by-line John Taverel, Howard penned ‘The Spirit of Tom Molyneaux,’ a story which combined boxing and ghosts, published as ‘The Apparition in the Prize Ring’ in Ghost Stories. In July, he finally had a story published in Argosy after years of trying: ‘Crowd-Horror’ is a psychological thriller about a slugger who is transformed by the yells of the crowd from a clever and skillful boxer to a wild-swinging brute. More importantly, in July 1929, Fight Stories published the first of his Sailor Steve Costigan stories, about a roistering merchant seaman who battles his way around the world as he is caught up in one comic mishap after another.

Several critics have noted that Howard’s writing can be divided into ‘periods.’ Though they overlap to some degree, these periods may reveal something about Howard’s style and methods. The most well-defined phases are those during which he wrote boxing stories, culminating in the Steve Costigan series; heroic fantasies, culminating with Conan; oriental adventures, culminating in El Borak; and western yarns. He was still ‘in’ the western period at the time of his death. A close reading of Howard’s letters and stories reveals that he would develop an interest in a subject and immerse himself in it so thoroughly that he adopted a new persona, or fictional identity, the voice through which he spoke as a writer. While something of the pattern can be seen in his early writing, it is most apparent in his ‘boxing’ persona, Steve Costigan.

Just when Robert Howard developed his passion for boxing is not clear, but certainly by the time he met Clyde Smith in Brownwood it was strong. He boxed with his friends at any opportunity, and may have occasionally assisted in promoting fights at local clubs in Cross Plains. While working at the soda fountain at Robertson’s Drug Store, he befriended an oil-field worker who introduced him to the amateur fighters at the local ice house.

He soon became a frequent participant in these bouts. Between 1925 (at the latest) and 1928, Howard put himself through a weight and strength program, and took on really heroic proportions. He read avidly about prizefighters and attended matches whenever and wherever he could. By early 1929 he had begun writing and submitting boxing stories, with his first efforts mingling boxing with weird themes (presumably a field in which he knew he could sell). With the first Steve Costigan story, ‘The Pit of the Serpent,’ in the July 1929 Fight Stories, he had found a market that would prove as steady for him as Weird Tales, at least until the Depression KO’d Fight Stories and its companion magazine Action Stories in 1932.

During the same summer weekend in 1927 when he met Harold Preece in Austin, Howard bought a copy of G. K. Chesterton’s The Ballad of the White Horse. This epic poem brings together Celts, Romanized Britons and Anglo-Saxons under King Alfred in a battle that pitted Christians against the heathen Danish and Norse invaders of the 9th Century. Howard enthused about the poem in letters to Clyde Smith, sharing lengthy passages. It seemingly inspired him to begin work on ‘The Ballad of King Geraint,’ in which various Celtic peoples of early Britain make a valiant ‘last stand’ against the invading Angles, Saxons and Jutes. Chesterton’s concept of “telescoping history,” that “it is the chief value of legend to mix up the centuries while preserving the sentiment,” must have appealed to Howard. This is precisely what he did in many of his fantasy adventures, particularly in the creation of Conan’s Hyborian Age, which conflates vastly different historical eras and cultures: from medieval Europe (Aquilonia and Poitain) to the American frontier (the Pictish Wilderness and its borderlands), and from Cossacks (the Kozaki) to Elizabethan pirates (the Free Brotherhood). This historical melting pot allowed Howard to portray what he saw as universal elements of human nature as well as giving him nearly all of human history for a playground.

When Howard discovered that Harold Preece shared his enthusiasm for matters Celtic, he entered into his ‘Celtic’ phase with his customary brio. His letters to Preece and to Clyde Smith from 1928 to 1930 are full of discussions of Irish history, legend and poetry – he even taught himself a smattering of Irish Gaelic and began exploring his genealogy in earnest. Irish and Celtic themes came to dominate his poetry and by 1930 he was ready to try out this new persona with fiction. In keeping with his tendency to use old material as a springboard into new, he first introduced an Irish character into a story featuring two earlier creations. Cormac of Connacht is often overlooked as one of the ‘Kings of the Night,’ as he is overshadowed in this tale by the alliance between Bran Mak Morn and King Kull, but the story of a battle against the encroaching Roman legions is told from the Irish King Cormac’s point of view.

During 1930, Howard wrote a number of stories featuring Gaelic heroes, nearly all of them outlawed by clan and country. Turlogh Dubh O’Brien and Cormac Mac Art are reivers of the 11th century, who fight alongside Danes or Saxons in their battles with other northern seafarers. While he was able to sell two stories of Turlogh to Weird Tales – ‘The Dark Man’ and ‘The Gods of Bal-Sagoth’ – Howard was unsuccessful in marketing the Cormac tales, as they did not feature any ‘weird’ elements (although he did leave one unfinished Cormac story with a supernatural theme).

In June 1930, Howard received a letter from Farnsworth Wright informing him that Weird Tales planned to launch a sister magazine dealing with oriental fiction, and asking him to contribute. This request revived the author’s avid interest in the Orient, particularly the Middle East, and he produced some of his finest stories for the new magazine, Oriental Stories.

The magazine changed its title to The Magic Carpet Magazine in 1933 and ceased publication with the January 1934 issue. While these stories were set during the Crusades, or periods of Mongol or Islamic conquests, they invariably featured Celtic heroes. One of these was Cormac FitzGeoffrey, a Norman-Irish Crusader whom Howard called “the most somber character I have yet attempted,” a true understatement. “Cormac had seldom known an hour’s peace or ease in all his 30 years of violent life. Hated by the Irish and despised by the Normans he had payed back contempt and ill treatment with savage hate and ruthless vengeance.” Cormac may well be Howard’s most sociopathic character, venturing deeper into “the dark heart of human violence” than any other, although Cahal Ruadh O’Donnel (of ‘Sowers of the Thunder’) and Donald MacDeesa (of ‘Lord of Samarcand’) give him a run for his money. So does John Norwald, the Englishman whose hate keeps him alive for 23 years, to wreak a grim vengeance upon ‘The Lion of Tiberias.’

In August 1930, Howard wrote to Farnsworth Wright in praise of H.P. Lovecraft’s ‘The Rats in the Walls,’ which had just been reprinted in Weird Tales. In the letter, he noted the use of a phrase in Gaelic, suggesting that Lovecraft might hold to a minority view on the settling of the British Isles. Wright sent the letter on to Lovecraft, who frankly had not supposed that anyone would notice the liberty he had taken with his archaic language. He wrote to Howard to set the record straight, and thus began what is surely one of the great correspondence cycles in all of fantasy literature. For the next six years, Howard and Lovecraft debated the merits of civilization versus barbarism, cities and society versus the frontier, the mental versus the physical, art versus commerce, and many other subjects. At first Howard was deferential to Lovecraft, whom he (like many of his colleagues) considered the pre-eminent writer of weird fiction of the day. But gradually Howard came to assert his own views more forcefully, and eventually could direct withering sarcasm toward Lovecraft’s own attitudes, such as noting how ‘civilized’ Italy was in bombing Ethiopia in 1935 (Lovecraft was an admirer of the social policies of Mussolini and the Fascists).

These letters are a mine of information on Howard’s travels and activities during these years, as well as his views on many subjects. They also highlight Howard’s growing interests in regional history and lore, an interest which was greatly fostered by Lovecraft, E. Hoffmann Price (the only writer from the Weird Tales stable to meet him in person) and August Derleth. They reveal the development of a new persona, that of ‘The Texian’ (a term used for Texans prior to statehood), which would come to increasingly dominate Howard’s fiction and letters in the latter part of his life. It is unfortunate that this persona did not have a chance to mature, as his letters suggest that he would have made one hell of a western writer.

Even before Howard bought his own car in 1932, he and his parents travelled widely around Texas, to visit friends and relatives, and for his mother’s health, which was in serious decline. After he bought his Chevrolet sedan, his friends Lindsey Tyson and Truett Vinson joined him on excursions further afield, from Fort Worth to the Rio Grande Valley, and from the East Texas oil fields to New Mexico. His letters to Lovecraft describe much of the geography and history of these places, and are interesting travelogues, quite apart from being windows into Howard’s life.

His correspondence with Lovecraft seems to have inspired the young writer to attempt stories similar to those of the acknowledged master. One such early effort, ‘The Children of the Night,’ also brings together some key Howardian elements such as racial memory and race hatred, a Celtic warrior and a primitive subterranean race. Other Lovecraft-styled stories followed, such as ‘The Thing on the Roof’ and ‘The Black Stone,’ introducing Howard’s own contributions to the ‘Cthulhu Mythos,’ in the form of Von Junzt and his hellish ‘Black Book,’ Nameless Cults (later dubbed Unaussprechlichen Kulten), and the mad poet Justin Geoffrey. The Lovecraft influence was the final ingredient needed in the rich imaginative mix that produced Howard’s most popular and enduring work – his tales of Conan the Cimmerian.

In a letter to Lovecraft in April 1932, Howard outlined his latest creation: “I’ve been working on a new character, providing him with a new epoch – the Hyborian Age, which men have forgotten, but which remains in classical names, and distorted myths. [Farnsworth] Wright rejected most of the series, but I did sell him one – ‘The Phoenix on the Sword’ which deals with the adventures of King Conan the Cimmerian, in the kingdom of Aquilonia.” In a postscript to the same letter, he wrote: “Wright took another of the Conan the Cimmerian series, ‘The Tower of the Elephant,’ the setting of which is among the spider-haunted jeweled towers of Zamora the Accursed, while Conan was still a thief by profession, before he came into the kingship.”

Much later, Howard would tell a fan that “Conan simply grew up in my mind a few years ago when I was stopping in a little border town on the lower Rio Grande. I did not create him by any conscious process. He simply stalked full grown out of oblivion and set me at work recording the saga of his adventures.” To fellow author Clark Ashton Smith he said, “While I don’t go so far as to believe that stories are inspired by actually existent spirits or powers (though I am rather opposed to flatly denying anything) I have sometimes wondered if it were possible that unrecognized forces of the past or present – or even the future – work through the thoughts and actions of living men. This occurred to me when I was writing the first stories of the Conan series especially. I know that for months I had been unable to work up anything sellable. Then the man Conan seemed suddenly to grow up in my mind without much labor on my part and immediately a stream of stories flowed off my pen – or rather, off my typewriter – almost without effort on my part. I did not seem to be creating, but rather relating events that had occurred. Episode crowded on episode so fast that I could scarcely keep up with them. For weeks I did nothing but write of the adventures of Conan. The character took complete possession of my mind and crowded out everything else in the way of story-writing.”

While it wasn’t quite as effortless as Howard makes out, there is no doubt that Conan is one of Howard’s most fully realized characters. The “little border town” where he first appeared to the author is in all likelihood Mission, Texas, where the Howards visited in early 1932. On the typescript of Howard’s poem, ‘Cimmeria,’ which he sent to Emil Petaja was the comment “Written in Mission, Texas, February 1932; suggested by the memory of the hill-country above Fredericksburg seen in a mist of winter rain.” Apparently that “endless vista – hill on hill, slope beyond slope, each hooded like its brothers” triggered something in the subconscious of the writer. The first line of the poem is “I remember.” He explained to Smith: “Some mechanism in my sub-consciousness took the dominant characteristics of various prize-fighters, gunmen, bootleggers, oil field bullies, gamblers, and honest workmen I had come in contact with, and combining them all, produced the amalgamation I call Conan the Cimmerian.”

As with previous characters, however, Conan’s first adventure was not an original one. Following a tried and true pattern, Howard dusted off an unsold King Kull story, ‘By This Axe I Rule!’ and added a weird element and background about Conan. The end result was ‘The Phoenix on the Sword’ (December 1932), in which the readers of Weird Tales were introduced to the Cimmerian, who would, for the next three years, rival Seabury Quinn’s occult detective Jules de Grandin as the most popular character in the magazine. The Hyborian Age, Howard’s telescoped composite of human history and cultures, allowed him free range to place his character in myriad settings, to explore human nature and history, and to try out new types of stories.

In the spring of 1933, Howard took on Otis Adelbert Kline as his agent, continuing to deal directly only with Weird Tales. Under Kline’s prodding, and because his need for money was made more urgent by his mother’s worsening health and attendant medical expenses, Howard began ‘splashing the field,’ trying to write as many different types of stories for as many different magazines as he could. Conan, because he could range freely throughout the world, provided a useful vehicle for a writer trying his hand at new types of fiction. Thus we have a Conan detective story (‘The God in the Bowl’), Conan pirate stories (‘The Pool of the Black One,’ ‘The Black Stranger’), Conan frontier stories (‘Beyond the Black River’), and several Conan oriental adventures (‘A Witch Shall Be Born,’ ‘The Man-Eaters of Zamboula,’ ‘People of the Black Circle’).

Conan’s – and his creator’s – career was very nearly cut short by an automobile accident. On the night of December 29, 1933, Howard and three friends were returning from Brownwood on a foggy, rainy night, when Robert ran his car head-on into a flagpole, painted grey and set in concrete in the middle of the street, in the town of Rising Star. One companion was thrown through the windshield, another suffered an injured leg. Howard himself was “driven against the wheel with such terrific force that I crumpled it with my breast-bone,” and was gashed across his jaw by a shard of glass, laying bare the bone. “All parties made rapid and uneventful recoveries,” Howard wrote.

“The town where the accident occurred helped me pay for having my car repaired, and the flagpole has been removed – though one of their own citizens had to wreck himself on it before that was done.”

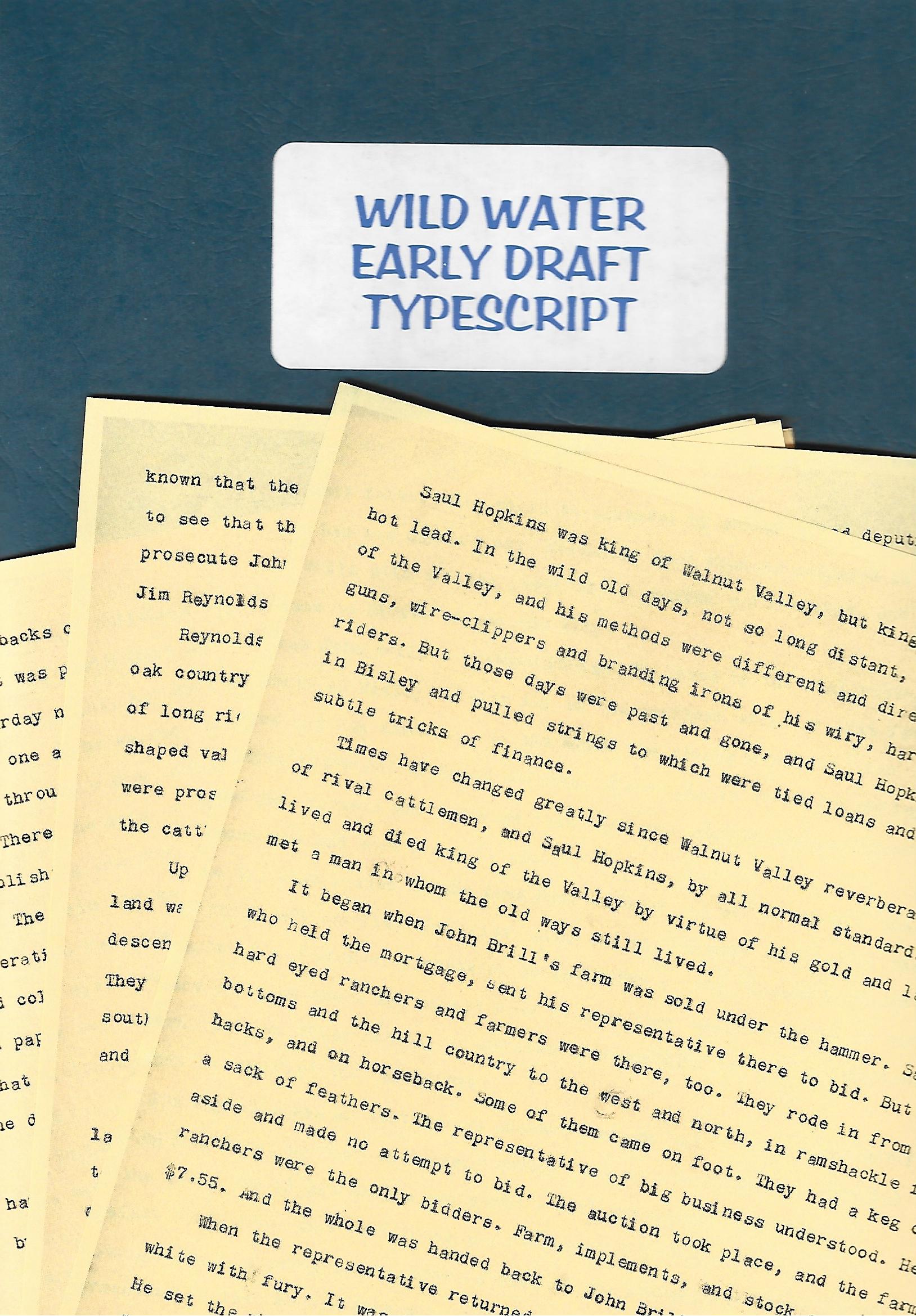

By 1932, Howard had turned his attention closer to home and, along with his friend Clyde Smith (who went on to write several books of local history) he had begun to explore the pioneer days of Texas. At first he wrote several very good weird stories with a regional background, such as ‘The Horror from the Mound,’ ‘Old Garfield’s Heart,’ and ‘The Man on the Ground.’ However, in 1934, his most successful western hero, Breckenridge Elkins of Bear Creek, Nevada, burst onto the scene. Elkins was a huge mountain of a man whose rollicking adventures recall the tall tales of Pecos Bill. True to form, Howard started with a familiar scenario. ‘Mountain Man,’ which appeared in the March/April 1934 issue of Action Stories, has Elkins mixed up in a prize-fight due to a case of mistaken identity. It’s a Steve Costigan yarn transplanted to a Western frontier town with dialogue that crackles with wit and an uncanny ear for local dialects. The story’s delightful, earthy sense of humor shows another side of Howard, and one with which most readers, who are inclined to think of him as dark and brooding, are sadly unfamiliar. Breckenridge Elkins appeared in every issue of Action Stories for over two years and proved so popular that when the editor moved over to Argosy, he asked Howard to create another series along the same lines for that magazine.

Also in 1934, a new schoolteacher arrived in Cross Plains, who would play a major role in Robert E. Howard’s life. He had met Novalyne Price a little over a year earlier after being introduced to her by their mutual friend Clyde Smith. Upon moving to Cross Plains, Novalyne made several attempts to call Howard, only to be told by his mother that he could not come to the phone or was out of town. At last, tiring of these brush-offs, she talked her cousin into giving her a ride to the Howard home, where she was greeted rather coolly by his father but somewhat more eagerly by Robert. This was the start of a sometimes affectionate, sometimes stormy relationship.

For the first time there was someone locally who shared Howard’s interests – and she was a woman! However, his insistence upon personally caring for his ailing mother, whom Novalyne felt would benefit more from the services of a professional nurse, rankled at her, as did his refusal to attend social events. Marriage often entered their minds and was even occasionally discussed, but they did not entertain the same feelings at the same time. When she would think she was in love, he would insist he needed his freedom. When he thought he was ready for love, she saw only their differences. They were both passionate, fiercely independent people, which made for an intense and exciting relationship, but one that was impossible to sustain. In the spring of 1936, Novalyne was accepted into the graduate program in education at Louisiana State and left Cross Plains.

It has been argued that the strong-willed young schoolteacher may have inspired Howard’s creation of his feisty women warriors, particularly Dark Agnes de la Fere (‘Sword Woman’) and Valeria of the Red Brotherhood (‘Red Nails’), but this cannot be entirely the case. As early as 1928, ‘The Isle of Pirates’ Doom’ had featured the swashbuckling Helen Tavrel, who boasted, “I am probably the finest pistol shot in the world, but the blade is my darling.” Then there’s Bêlit, the ‘Queen of the Black Coast,’ leader of a band of corsairs that roamed the Hyborian Age seas, and Conan’s first love. And in ‘The Shadow of the Vulture’ (Oriental Stories, January 1934) appeared Red Sonya of Rogatino, the fiery-tressed Russian who is found in the thick of the fighting during Suleyman the Great’s siege of Vienna in 1529 (armored somewhat more appropriately than her comic-book namesake). However, Valeria, and especially Agnes, assert most positively Howard’s proto-feminist views. “Ever the man in men!” cries Agnes, when Guiscard de Clisson urges her to don her petticoats. “Let a woman know her proper place; let her milk and spin and sew and bake and bear children, not look beyond her threshold or the command of her lord and master! Bah! I spit on you all! There is no man alive who can face me with weapons and live, and before I die, I’ll prove it to the world!”

While Novalyne’s refusal to accept the stereotypical role of wife and homemaker no doubt made some impact on Howard, it is clear that his progressive views on women stretched further back. A lengthy letter to Harold Preece in 1928 is an impassioned defense of women: “Men have sat at the feet of women down the ages and our civilization, bad or good, we owe to the influence of women.” Though many of his female characters are merely props (as are many of the men), it is evident that Howard, perhaps in response to his mother’s influence, was more sympathetic to women than might be expected from a man of his time. Indeed, some of the top women fantasy writers, such as C.L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, Jessica Salmonson, and Nancy Collins, have expressed their admiration for Dark Agnes de la Fere.

Through 1935 and 1936, Howard’s mother’s health deteriorated rapidly. Increasingly, she had to be taken to sanitariums and hospitals, and even though Dr. Howard received a discount on services, the medical bills began to mount. Robert was faced with a dilemma – his need for money was more acute than ever, but he had little time in which to earn it. Weird Tales owed him around $800, and payments were slow. With his own meager savings exhausted, Dr. Howard moved his practice into his home, which meant that patients were now coming and going day and night. Father and son finally hired women to nurse and keep house, but this further filled their home with people and provided Robert little opportunity to be alone and concentrate on his writing. This, combined with the despair he felt as his mother inexorably slid towards death, placed enormous stress upon the young writer, and he resurrected an apparently long-standing plan not to outlive his mother.

This was no impulsive act. For years he had told associates such as Clyde Smith that he would kill himself were it not that his mother needed him. Much of his poetry, most of it written during the 1920s and early 1930s, forcefully reflects his suicidal frame of mind. He was not at all enamored with life for its own sake, seeing it only as a weary slog at the behest of others, with scant chance of success and precious little freedom. On one occasion, in 1925, he had written to Smith, at a time when he thought he had let his friends down:

“I sat and thought. My thoughts ran, shall I live and continue to be a failure, to grind my life out and at last pass on, a failure, among failures”

“I really never expected to leave that office when I entered it, alive.”

A 1931 letter to Farnsworth Wright contains several statements of common Howard themes: “Like the average man, the tale of my life would merely be a dull narration of drab monotony and toil, a grinding struggle against poverty… Life’s not worth living if somebody thinks he’s in authority over you… I’m merely one of a huge army, all of whom are bucking the line one way or another for meat for their bellies… Every now and then one of us finds the going too hard and blows his brains out, but it’s all in the game, I reckon.” Howard’s letters frequently express the feeling that he was a misfit in a cold and antagonistic world: “The older I grow the more I sense the senseless unfriendly attitude of the world at large.” In nearly all his fiction, the characters are strangers or outcasts in a hostile land. One wonders if his childhood experience of being uprooted on a regular basis as his father gambled on one boom town after another may have contributed to this sense of himself as an outsider. In some of his letters to Lovecraft he expressed another variation on this theme: the feeling that he was somehow born out of his proper time. One cause of their ‘barbarism vs. civilization’ debate was Howard’s expressed wish that he’d been born during the barbaric epoch in Germany or Gaul; he frequently bemoaned the fate that had him arrive too late to have participated in the taming of the frontier. “I only wish I had been born earlier – thirty years earlier, anyway. As it was I only caught the tag end of a robust era, when I was too young to realize its meaning. When I look down the vista of the years, with all the ‘improvements,’ ‘inventions’ and ‘progress’ that they hold, I am infinitely thankful that I am no younger. I could wish to be older, much older. Every man wants to live out his life’s span. But I hardly think life in this age is worth the effort of living. I’d like to round out my youth; and perhaps the natural vitality and animal exuberance of youth will carry me to middle age. But good God, to think of living the full three score years and ten!”

Howard also seems to have abhorred the idea of growing old and infirm. A month before his death he’d written to August Derleth: “Death to the old is inevitable, and yet somehow I often feel that it is a greater tragedy than death to the young. When a man dies young he misses much suffering, but the old have only life as a possession and somehow to me the tearing of a pitiful remnant from weak fingers is more tragic than the looting of a life in its full rich prime. I don’t want to live to be old. I want to die when my time comes, quickly and suddenly, in the full tide of my strength and health.”

For a young man, Howard seems to have had an exaggerated sense of growing old. When he was only 24 he wrote to Harold Preece, “I am haunted by the realization that my best days, mental and physical, lie behind me.” Novalyne Price recalls that during the time they were dating, between 1934 and 1935, Howard often said that he was in his “sere and yellow leaf,” echoing a phrase from Macbeth: “I have lived long enough, my way of life | Is fal’n into the sere, the yellow leaf…”

Also in his May 1936 letter to Derleth, Howard mentioned that “I haven’t written a weird story for nearly a year, though I’ve been contemplating one dealing with Coronado’s expedition on the Staked Plains in 1541.” This suggests that ‘Nekht Semerkeht’ may well have been the last story Howard started and, significantly, it dwells upon the idea of suicide. “The game is not worth the candle,” thinks the hero, de Guzman.

“Oh, of course we are guided solely by reason, even when reason tells us it is better to die than to live! It is not the intellect we boast that bids us live – and kill to live – but the blind unreasoning beast-instinct. “Hernando de Guzman did not try to deceive himself into believing there was some intellectual reason, then, why he should not give up the agonizing struggle and place the muzzle of his pistol to his head; quit an existence whose savor had long ago become less than its pain.”

Howard planned for his death very carefully. He made arrangements with his agent, Otis Kline, for the handling of his stories in the event of his death. He carefully assembled the manuscripts he had yet to submit to Weird Tales or the Kline agency, with instructions on where they were to be sent. He borrowed a gun, a .380 Colt automatic, from a friend who was unaware of his intentions. His father may have hidden Robert’s own guns, aware of what he might be contemplating. He said that he had seen his son make preparations on earlier occasions when it appeared Mrs. Howard might die and that he tried to keep an eye on Robert, but did not expect him to act before his mother died.

Hester Howard sank into her final coma around the 8th June, 1936. On the 10th, Robert went to Brownwood and purchased a cemetery lot for three burials, with perpetual care. He asked Dr. J. W. Dill, a friend of his father’s who had come to be with Dr. Howard during his wife’s final illness, whether anyone had been known to live after being shot through the brain. Unaware of Robert’s plan, the doctor told him that such an injury meant certain death. The night before, Robert had disarmed his father of his deadly intent, assuming “an almost cheerful attitude… He came to me in the night, put his arm around me and said, buck up, you are equal to it, you will go through it all right.” On the morning of the 11th, Robert asked the nurse attending Mrs. Howard if she thought his mother would ever regain consciousness, and was told she would not.

He then walked out of the house and got into his 1935 Chevy. The hired cook stated later that she saw him raise his hands in prayer. Was he praying or preparing the gun? She then heard a shot, and saw Robert slump over the steering wheel. She screamed. Robert’s father and Dr. Dill ran out to the car and carried his limp body back into the house. He had shot himself above the right ear, the bullet emerging on the left side of his head. Robert Howard’s robust health allowed him to survive this terrible wound for almost eight hours. He died at around 4:00 pm, Thursday, June 11, 1936, without ever regaining consciousness. His mother died the following day, also without regaining consciousness. A double funeral was held on June 14, and the mother and son were transported to Greenleaf Cemetery in Brownwood for burial.

It is a regrettable postscript that Robert E. Howard’s suicide has tended to color interpretations of his mental health. While it is hard to maintain that killing oneself at the age of 30 is ‘normal’ behavior, suicide is often a very complex response to real or perceived problems. There are many reasons people take their own lives, and not all of them are rooted in grief, despair or depression. It is doubly unfortunate, in Howard’s case, that his action coincided with his mother’s death, which has led to the inevitable, but in my view simplistic notion that he killed himself out of despondency. This has, in turn, led to the supposition – without any compelling evidence – that he was ‘unnaturally’ close to or dependent upon his mother. It may well be that, had he not been needed to care for his mother, Robert would have taken his life even earlier. Or it may be that, had there been a friend with him to see him through the crisis, Robert would have carried on after her death. We can never really know. To link his suicide solely with his mother’s death, though, is to ignore a host of other contributing factors.

Opinions on Howard’s state of mind vary wildly, from ‘psychotic’ and ‘Oedipal’ to suggestions that he was a pretty normal guy who succumbed to stress. By his own testimony in letters, as well as the statements of his friends, we know he was certainly subject to dark moods. On the other hand, the memoirs of those who knew him best – Tevis Clyde Smith, Novalyne Price (Ellis) and Harold Preece – show they thought the world of him, and on balance he was an intelligent and affable companion. If he was occasionally eccentric in his dress or actions, it may have been as Novalyne Price told her roommate: “He’s trying to tell people he’s a writer and writers have a right to be odd. Since they think he’s crazy, anyway, he’ll show them just how crazy he can be.”

This attitude is indeed reflected in some of Howard’s letters to Smith and Preece. It is interesting to note that most of the speculation about Howard’s mental health has come from people with minimal or no qualifications in this area. One person who is qualified, Charles Gramlich, a professor of psychology and fantasy author, wrote: “No matter how much some folks seem to want to think Howard was crazy, it just ain’t so. Call him eccentric and I’ll go along with that. Call him crazy in the way that some of us call ourselves crazy, and I’ll buy that. But he was not clinically disturbed… In my opinion, Howard was no crazier than the rest of us. He was just a better writer.”

Dr. Isaac M. Howard survived his wife and son by eight years. He had developed diabetes, and his worsening health forced him to cease practicing and move, in 1940, to Ranger, Texas, where Dr. P.M. Kuykendall had invited him to live with his family and assist him at the West Texas Clinic & Hospital. He died in November 1944, leaving his estate to Dr. Kuykendall.

Following Howard’s death, Weird Tales published a number of his stories for a few more years, until Farnsworth Wright stepped down as editor. In 1946, August Derleth, through his Arkham House imprint, originally established to publish the work of H. P. Lovecraft in book form, brought out a collection of Howard’s best stories, titled Skull-Face and Others.

A small magazine, the Avon Fantasy Reader, included several Howard stories in its 18-issue run during the late 1940s, and in the early 1950s, a science fiction and fantasy publisher, Gnome Press, brought out the Conan stories in hardback. In the 1960s, Conan paperbacks, with dynamic covers by Frank Frazetta, brought Robert E. Howard a measure of fame equal to that of J.R.R. Tolkien and Edgar Rice Burroughs. In the 1970s, shepherded by Glenn Lord, a ‘Howard boom’ erupted and readers became aware of the tremendously varied range of the prolific writer’s output.

This boom period extended into the next decade thanks to the comic books and magazines that were nominally devoted to Conan, but occasionally featured Howard’s other characters or stories and published articles about the author and his work. In the 1980s, Conan came to the screen, though in a manner scarcely recognizable as Howard’s, catapulting the character to worldwide recognition. At the same time, a growing movement among writers and critics of fantasy fiction had begun to take Howard’s work seriously as literature, rather than dismissing it as mere escapist fare.

Toward the end of the ‘80s, Project Pride, a community organization in Cross Plains, purchased the Howard home and through their efforts and those of his fans around the world, the author’s house is now restored and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Each June, Project Pride and the City of Cross Plains sponsor Robert E. Howard Day, and welcome the many visitors who come to tour the Howard House and see first-hand the environment in which the author lived.

By the time of his death, Robert E. Howard had been spinning his tales of myth and mystery for a mere dozen years, only four of which he devoted to his most famous creation, Conan. Yet today, over 60 years after his death, the adventures of the Hyborian hero and much of Howard’s other work endures. Unlike many of his contemporaries writing for the pulps, Howard’s fertile imagination and powerhouse storytelling gains him new fans in each successive generation. His work has inspired countless imitations and has been translated not only into many other languages, but into other media as well – comics, movies, television. In their wake have followed fan clubs and publications, an amateur press association founded in 1972 and still going strong, and now a growing presence on the World Wide Web. Truly, Robert E. Howard, like Conan, is one for the ages.